by Al Drinkle

An ex-colleague of ours often cited an aphorism when we were considering the importation of new wines. Sometimes he would use it rhetorically, and sometimes just as food for thought, but it was almost a given that at some point during the assessment of samples, Matty “Malo Matt” Leslie would quip, “hmmmmm… well… is this the hill that we're willing to die on?”. And in the case that he was vehemently against working with said wines, he'd state, “I'm not dying on that hill!".

To give some context, the current rates of shipping are such that if we're not filling every nook and cranny on a pallet, our customers end up paying more for the transport of the bottles than for the actual wine inside of them. So when we're considering the initiation of a new relationship, we're effectively deciding if we like the wines enough to commit to a minimum of 600 bottles, more or less. In the case of an unknown producer, an obscure region, grape varietals outside the mainstream, unusually expensive products, or any combination of these, we're committing to a challenge — a battle, if you will, and a hill that we must be willing to die on. For example, France's underappreciated Southwest? Yes, we'll take on that battle. German Riesling in Cabernet-swilling Alberta? Absolutely; in fact we've been clanging swords on that hill for so long that we wouldn't even know how to stop. Sherry? If we end up perishing on that particular hill, it would be a noble and worthwhile death.

A couple of months ago, the Metro Mates congregated to taste the samples from a fledgling Spanish producer. Each of the wines were from the Sierra de Salamanca — up in the mountains between Madrid and the Portuguese border — and made entirely from the Rufete grape. (If the place and grape are both unfamiliar to you, you’re in good company). They all had lovely labels, which is welcome but not essential, and none of them were particularly inexpensive. But from each bottle we encountered ravishing red fruit, wild florality, caressing and savoury textures, brisk and playful freshness and an enchanting sense of purity, all combined in a way that we had never quite experienced before. Somebody quoted Malo Matt's immortal question, and in answer, we all donned our chainmail, sharpened our blades, bid our loved ones farewell and crested the hill where we would proudly engage in combat on behalf of Malahierba's Salamanca Rufete.

Malahierba is a partnership between Silvia Rocher and Manuel Garcia, both of whom are certified agricultural engineers. Manuel is a native of the Sierra de Salamanca, where he and his brothers have always made wine for family consumption. Silvia, who is from Madrid, visited the Sierra for the first time in 2012 and was immediately smitten by the area. In addition to working harvests in as disparate places as New Zealand, California's Russian River Valley and Tuscany, she managed to keep her hand in a Sierra de Salamanca project through 2017, and got to know Manuel by crossing paths with him in the region. “He was always willing to help and to share his knowledge about the Sierra,” she says.

In 2018, the Sierra de Salamanca project that Silvia was involved with came to an end, which coincided with the birth of her daughter. She consequently took a year off of winemaking, and realizing how important the Sierra de Salamanca was to her, contacted Manuel to communicate her dream of a project focussed on the Rufete grape. “After five minutes of conversation, Malahierba Vinos was born,” she claims. Their first vintage was 2019.

When asked what it is about the Sierra de Salamanca that so appeals to her, Silvia responds: “The first time that I saw the terraced vineyards, I knew that it was something special. There are centennial micro-vineyards and a great diversity of soils and altitudes over a very small area.” The relative obscurity of the region must lend itself to upstart projects, I suggested. She agrees, stating that bit by bit they've been able to piece together vineyard sources that have never been touched by herbicides, and often planted with Rufete vines that — having survived the infiltration of the invasive Tempranillo — are often between 80 and 120 years old.

I had enjoyed Rufete prior to tasting Malahierba's wines, but my colleagues and I didn't know much about it. For example, despite also being found in parts of Portugal, why is it so at home in the Sierra de Salamanca? “King Alfonso VI commissioned Raimundo of Burgundy to repopulate several cities and provinces in what is now Spain, including Salamanca,” Silvia says. “A French colony arrived to these lands, establishing themselves in the south of the province which is why this area is still known as Sierra de Francia or Peña de Francia. We believe that this repopulation brought with it a grape that has evolved over the years to the Rufete that we know today.

“To us, Rufete is very similar to the Gamay grape or even Pinot Noir. In the Sierra, it can make wines that are very fluid and very easy to drink. Manuel and I love the red wines of Burgundy, Beaujolais, Loire and Galicia. We value freshness in red wines and Rufete is perfect for this style.” When I point out that, even for Rufete from Salamanca, Malahierba wines are particularly low in alcohol, she responds, “it's a challenge with global warming. We pick the grapes at low potential alcohol, but mostly to achieve the vibrant acidity that we value so much.”

By the way, “Malahierba” means “weeds”, in tribute to the diversity of plants and flowers found in vineyards that haven't been subjected to herbicide. Silvia and Manuel's wines are presently sourced from a mere 5 hectares worth of land, and thereby produced in rather small quantities. They are distinct, authentic and affable — eminently indicative of talented, passionate people who want the world to taste a special confluence of place and grape. Once you taste them, you'll understand why this is a hill that we're willing to risk our lives upon. As a final thought, Silvia notes, “the greatest success that we can imagine is making wines that people like — there is no greater emotion than that. It's gasoline for the soul!”.

2022 Malahierba Rufete $34

Manually harvested from bush-trained vines and fermented in used 420L chestnut barrels, this is the delightful introduction to Malahierba. Exuberant aromas of pink fruit and cool herbal tones give way to a palate of crunchy, early summer berries and a texture that's simultaneously vibrant and silky. To reference the regions that inspire Silvia and Manuel, this is more exotic than Beaujolais, more playful than Burgundy, less “purple and green” than Loire, and more supple than Galicia. It's unabashedly delicious and selflessly dynamic.

2020 Malahierba “Maleza” $43

Silvia claims that “San Esteban de la Sierra” is the village in their area that she loves the most, and from a 920m altitude granite parcel, they source the fruit for what is ultimately Malahierba's most elegant wine. "Maleza” refers to when a weed becomes leafy and more plantlike. After only a seven-day maceration, the wine spends 14 months in acacia barrels where it develops its caressing charm. The aromatics are polished and high-toned, like a regal confluence of cherries and lacquer, and the palate is a sustained and animated panoply of juicy berry fruit and ethereal sweetspice. It's amazing to think that this charmer is from Malahierba's second vintage ever… there's 569 bottles for the world.

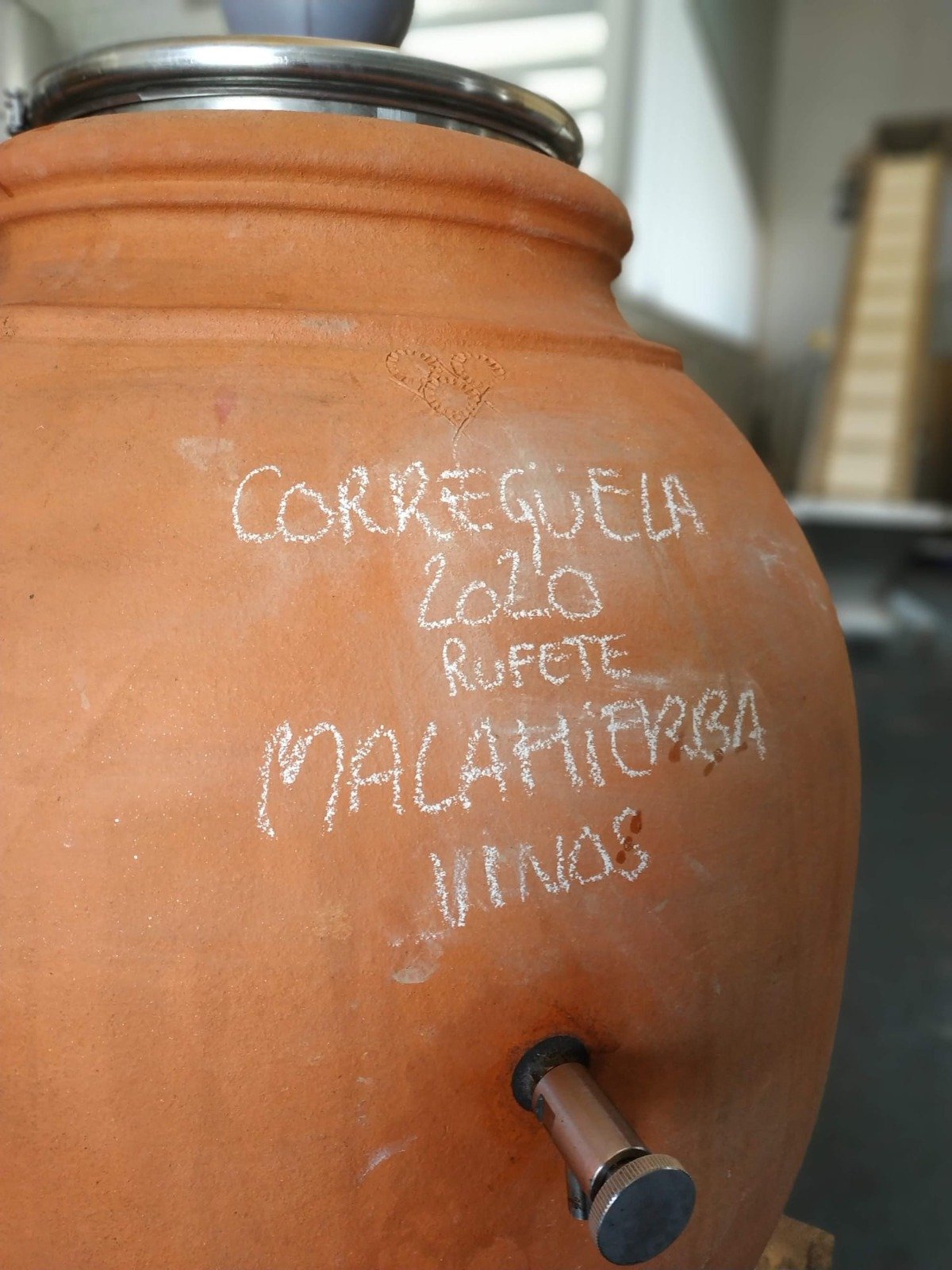

2020 Malahierba “Corregüela” $49

Grown at 1000 metres in altitude in the granite vineyards surrounding the village of Sanchotello, this enchanting expression of Rufete isn't quite within the limits of the Sierra de Salamanca PDO. No bother, for if you've got a quiet moment for it, it's the most intricate, mysterious and rewarding wine in the lineup. Sanchotella is the only town in the general region where amphorae have historical relevance, and Silvia and Manuel continue this tradition by giving the wine 22 months in clay. “Corregüela” refers to the bindweed that grows everywhere here. There were 269 bottles produced in total, and 60 of them found their way to Metrovino.